Children need to continue getting vaccinated against polio

This is the alert from Sespa on World Polio Day, to prevent the disease from returning to Brazil

On this Friday (24), when World Polio Day is celebrated, the State Department of Public Health (Sespa) reinforces the importance of children continuing to get vaccinated to keep the disease eradicated in Brazil.

The date was created by Rotary International to celebrate the birth of Jonas Salk, leader of the first team that developed a vaccine against polio. But the goal is to raise awareness about the disease, also known as polio or infantile paralysis, and emphasize that vaccination in early childhood is the only way to prevent the disease.

Another purpose is to inform the population about the dangers and severity of poliomyelitis and to gather efforts for the eradication of polio worldwide, as the virus still circulates in some countries.

Transmission, signs, and symptoms - Poliomyelitis is an acute infectious disease caused by the poliovirus, which lives in the intestine. Transmission occurs through direct contact with the feces or secretions expelled from infected individuals.

In most cases, infected individuals present symptoms similar to those of the flu, with fever and sore throat, or gastrointestinal infections, with nausea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain. However, they may also show no symptoms at all.

However, about 1% of those infected with the disease, mainly children under five years old, may suffer from severe forms of poliomyelitis. In these patients, the virus can attack the nervous system and cause permanent acute flaccid paralysis, respiratory failure, and even death. Generally, paralysis manifests in the lower limbs, affecting only one leg. The main characteristics of the sequelae are loss of muscle strength and reflexes, without loss of sensitivity.

Diagnosis can be confirmed through different laboratory tests, such as stool or secretions from the infected patient; tests for the detection of IgM antibodies in the blood; culture of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and electromyography to study the electrical activity of the paralyzed limb, in more severe cases.

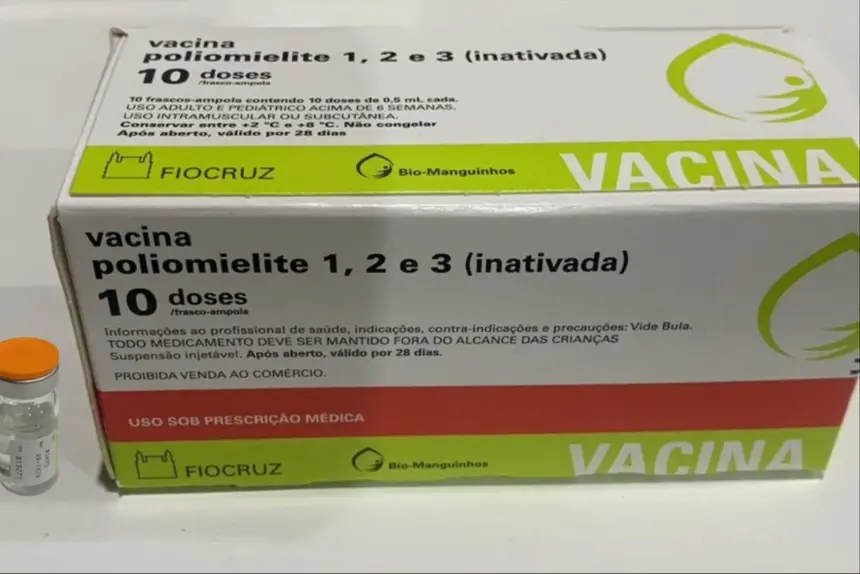

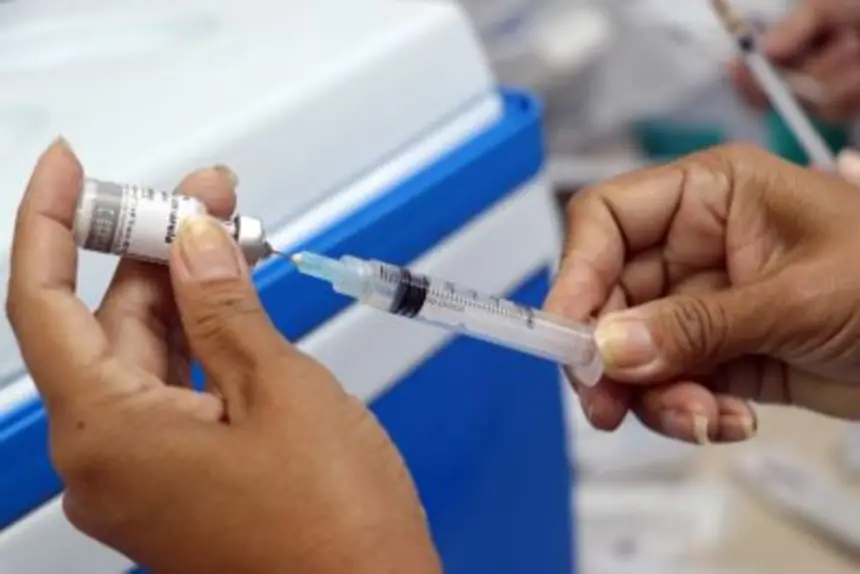

Prevention – There are two types of vaccines against poliomyelitis: the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) or Salk, administered intramuscularly; and the oral polio vaccine (OPV) developed by Albert Sabin, also known as Sabin or the drop vaccine.

However, the Sabin vaccine is being gradually phased out worldwide as part of the global strategy for disease eradication. This process is led by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO).

The reason for the change is that the OPV uses live attenuated viruses, and these viruses can, in rare cases, mutate and cause infantile paralysis in areas with low vaccination coverage.

The National Immunization Program (PNI) has already stopped using this type of vaccine in the basic vaccination schedule for children, adopting only the IPV in the complete scheme and booster. Therefore, the OPV is no longer being used in the State of Pará.

However, it is worth noting that the drop vaccine played a fundamental role in the eradication of the disease in Brazil, even inspiring the creation of Zé Gotinha, a character that remains important for mobilizing the population in favor of vaccination.

Eradication - In Brazil, there has been no circulation of wild poliovirus since 1990, thanks to the success of the prevention, surveillance, and control policy developed by the three levels of the Unified Health System (SUS). The last case of poliomyelitis was recorded in 1990, and Brazil received the Polio Eradication Certification in 1994. In Pará, the last case of the disease occurred in 1986, in the municipality of Santa Isabel.

According to the state coordinator of Immunizations at Sespa, Jaíra Ataíde, the absence of the disease and the lack of exposure to cases of paralysis lead some people to believe that the disease no longer exists. “This is not true, hence the importance of continuing to vaccinate children in early childhood.”

“Currently, the coverage of the IPV vaccine in Pará is at 70.24%, while the target is 95%, and the coverage of the booster is at 77%,” informed the state coordinator. “The low current vaccination coverage rates represent a risk of polio reappearing in the country,” she warned.

Jaíra Ataíde reminded that the basic vaccination schedule provides for the 1st dose of IPV at two months of age, the 2nd dose at four months, the 3rd dose at six months, and the booster at 15 months. “So, let’s take advantage of this date to share information about the importance of continuing to vaccinate children against poliomyelitis,” she concluded.